Neutrinos are the most abundant massive particles in the universe, and come from various natural sources - e.g. the sun, Supernova explosions, the Cosmic Microwave Background and cosmic rays, to name just a few. Since the 1960s, we have been mastering the techniques to make artificial neutrino beams with the help of particle accelerators. The advantage of making neutrino beams ourselves is that we can control many of the properties of the produced neutrinos and can use them to study processes at very specific energies.

To make a neutrino beam, we employ particle accelerators. Usually, we accelerate protons up to high energies (tens or hundreds of GeV) and then imping these protons onto specific targets (a common material for such targets is graphite, so essentially carbon). The protons will then interact with the nuclei inside the target and produce secondary particles, most commonly charged pions (and sometimes heavier particles such as kaons). We then use a series of magnets to focus the produced charged particles, which allows us to separate them by their charge. Pions and other such particles (called mesons) are short-lived and will quickly decay into more stable particles, producing neutrinos in the process which are broadly aligned with the incoming proton direction. However, unlike the charged pions, neutrinos are neutral particles and cannot be focused further. As a result, we obtain a beam of neutrinos, but the beam is not perfectly collimated.

Credit: Fermilab

Credit: Fermilab

Neutrino beams are particularly useful tools to study neutrinos - they allow us to produce neutrinos in a specific, relatively well-controlled energy range. Since the neutrino oscillation probability depends on the actual neutrino energy, having a good control over the energy of the neutrinos we produce allows us to study specific types of oscillations or create particles which have a specific mass. Beam neutrinos will oscillate as they propagate, and we can study how the composition of the beam changes at different propagation distances. The latter are what we refer to as the “baseline” of an experiment. Typically, we divide experiments which study beam neutrinos into long- and short-baseline experiments.

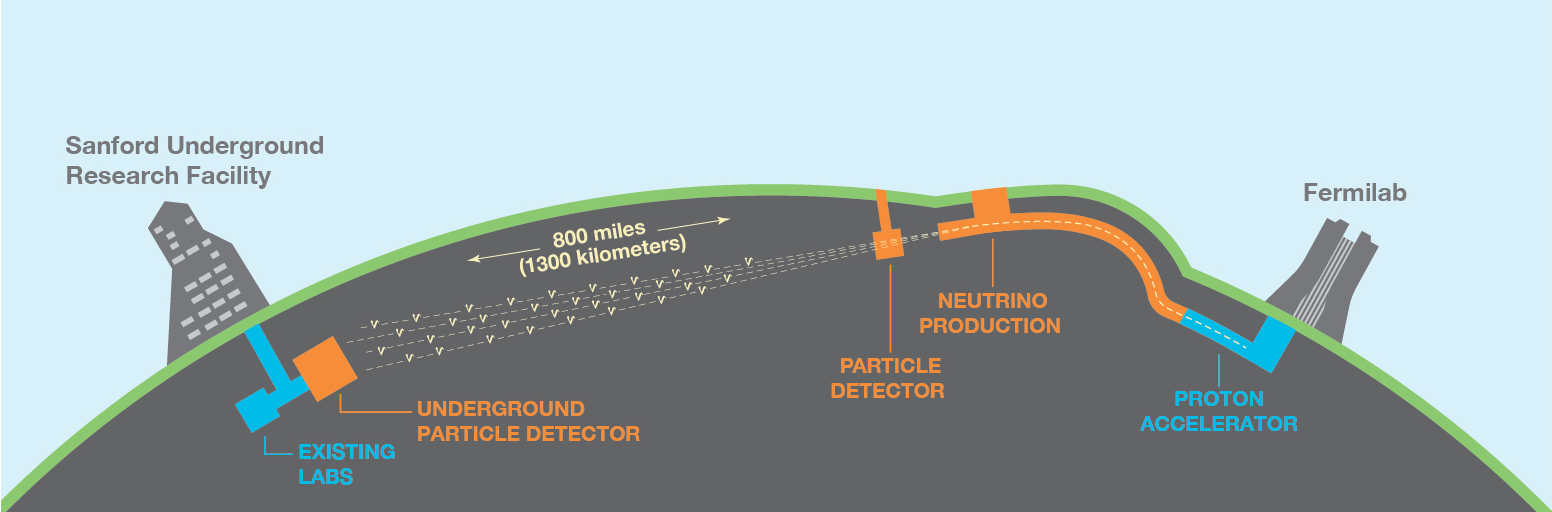

Long-baseline (LBL) neutrino oscillation experiments look for oscillations in a neutrino beam over distances of hundreds of kilometers. The neutrino (and thus accelerator) energies, as well as the baseline of the experiment, are chosen in a way in which we can maximize the probability of oscillation. Usually, the beams we produce are made almost exclusively of muon neutrinos (or anti-neutrinos), and during oscillations some of the muon neutrinos oscillate into electron or tau neutrinos. Examples of long-baseline experiments include the T2K and NOvA experiments (currently operating), and the future DUNE and Hyper-Kamiokande experiments. CERN is heavily involved in the T2K and DUNE experiments.

LBL experiments operate in the following way: after producing a muon neutrino or anti-neutrino beam, the composition of the beam is precisely measured with one or several detectors located close to the production point - these are called “near detectors”. At this point, oscillations are negligible and the near detectors allow us to characterize the beam that we produced. After the neutrinos have had time to propagate over the length of the baseline, they will have oscillated, and the new composition of the beam is measured with a “far detector”. The latter is typically very large, as the neutrino beam diverges significantly as the distance from the production point increases. One of the main strengths of LBL experiments is that they allow us to measure several oscillation parameters at once, including the still-unknown CP-violating parameter . Measuring certain values of this parameter could potentially be linked to explanations of the matter-antimatter asymmetry of the universe.

Credit: Fermilab, DUNE

Credit: Fermilab, DUNE

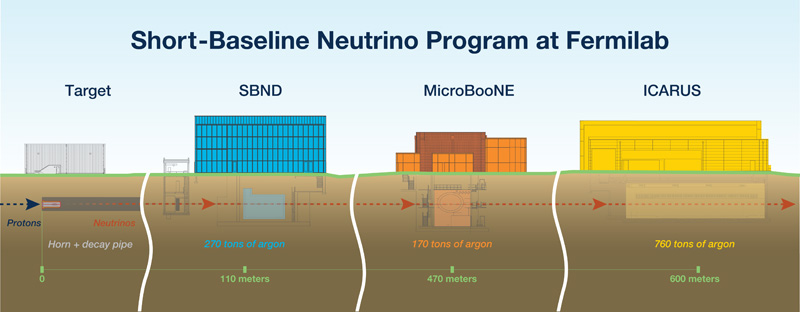

In addition to LBL experiments, neutrino beams can be used by so-called short-baseline (SBL) experiments. Such experiments have a similar operating principle to LBL experiments, but the typical baselines involved are of the order of a few hundred meters to a few kilometers. These distances are too short for standard flavor oscillations to occur, but they allow us to search for more exotic types of particles. For example, we have not yet ruled out the existence of so-called “sterile” neutrinos, which are neutrinos that do not interact through any of the forces we know, but do undergo oscillations. If such particles exist, then they would be able to oscillate over relatively short baselines and would alter the spectrum we expect to see with near detectors. Examples of SBL experiments are those in the Fermilab Short-baseline Neutrino (SBN) program, comprising the SBND, MicroBooNE and ICARUS detectors. CERN is heavily involved in the physics analyses with the ICARUS detector.

Credit: Fermilab

Credit: Fermilab

In addition to measuring neutrino oscillations, accelerator-based experiments can also measure neutrino interactions with matter. This is a crucial part of their physics program, because we currently do not have a good understanding of how neutrinos interact with atomic nuclei. Neutrinos themselves don’t leave any traces in our detectors as they propagate (since they are neutral), but they do interact with the detector materials and produce charged particles which do leave signatures in the detectors. By examining the types of neutrino interactions we can see, we can learn more about the nuclear physics we need in order to correctly simulate neutrino interactions with matter. If we make incorrect assumptions about the way in which neutrinos interact with matter, this could lead to incorrect measurements of the oscillation parameters we wanted to measure in the first place. The CERN EP-NU group plays a significant role in these studies for all accelerator-based neutrino experiments.